The Secret History of Hurricane KatrinaThere was nothing natural about the disaster that befell New Orleans in Katrina's aftermath.

— James Ridgeway

"Confronted with images of corpses floating in the blackened floodwaters or baking in the sun on abandoned highways, there aren't too many people left who see what happened following Hurricane Katrina as a purely "natural" disaster. The dominant narratives that have emerged, in the four years since the storm, are of a gross human tragedy, compounded by social inequities and government ineptitude—a crisis subsequently

exploited in every way possible for political and financial gain.

But there's an even harsher truth, one some New Orleans residents learned in the very first days but which is only beginning to become clear to the rest of us: What took place in this devastated American city was no less than a war, in which victims whose only crimes were poverty and blackness were treated as enemies of the state.

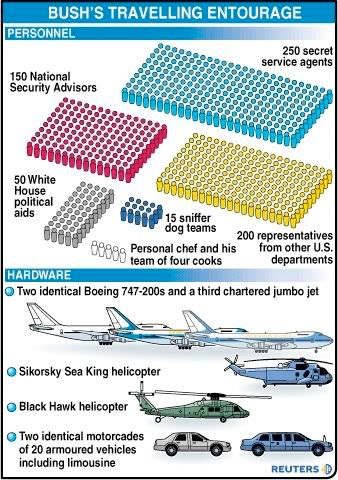

It started immediately after the storm and flood hit, when civilian aid was scarce—but private security forces already had boots on the ground. Some, like Blackwater (which has since redubbed itself Xe), were under federal contract, while a host of others answered to wealthy residents and businessmen who had departed well before Katrina and needed help protecting their property from the suffering masses left behind. According Jeremy Scahill's

reporting in The Nation, Blackwater set up an HQ in downtown New Orleans. Armed as they would be in Iraq, with automatic rifles, guns strapped to legs, and pockets overflowing with ammo, Blackwater contractors drove around in SUVs and unmarked cars with no license plates.

"When asked what authority they were operating under,'' Scahill reported, "one guy said, 'We're on contract with the Department of Homeland Security.' Then, pointing to one of his comrades, he said, 'He was even deputized by the governor of the state of Louisiana. We can make arrests and use lethal force if we deem it necessary.' The man then held up the gold Louisiana law enforcement badge he wore around his neck.''

The Blackwater operators described their mission in New Orleans as "securing neighborhoods," as if they were talking about Sadr City. When National Guard troops descended on the city, the Army Times described their role as fighting "the insurgency in the city." Brigadier Gen. Gary Jones, who commanded the Louisiana National Guard's Joint Task Force, told the paper, "This place is going to look like Little Somalia. We're going to go out and take this city back. This will be a combat operation to get this city under control."

Ten days after the storm, the New York Times

reported that although the city was calm with no signs of looting (though it acknowledged this had taken place previously), "New Orleans has turned into an armed camp, patrolled by thousands of local, state, and federal law enforcement officers, as well as National Guard troops and active-duty soldiers." The local police superintendent ordered all weapons, including legally registered firearms, confiscated from civilians. But as the Times noted, that order didn't "apply to hundreds of security guards hired by businesses and some wealthy individuals to protect property…[who] openly carry M-16's and other assault rifles." Scahill spoke to Michael Montgomery, the chief of security for one wealthy businessman who said his men came under fire from "black gangbangers" near the Ninth Ward. Armed with AR-15s and Glocks, Montgomery and his men "unleashed a barrage of bullets in the general direction of the alleged shooters on the overpass. 'After that, all I heard was moaning and screaming, and the shooting stopped. That was it. Enough said.'"

Malik Rahim, a Vietnam veteran and longtime community activist, was one of the organizers of the Common Ground Collective, which quickly began dispensing basic aid and medical care in the first days after the hurricane. But far from aiding the relief workers, Rahim told me this week, the police and troops who began patrolling the streets treated them as criminals or "insurgents." African American men caught outside also ran the risk of crossing paths with roving vigilante patrols who shot at will, he says. In this dangerous environment, Common Ground began to rely on white volunteers to move through a city that had simply become too perilous for blacks.

In July, the local television station WDSU

released a home video, taken shortly after the storm hit, of a local man, Paul Gleason, who bragged to two police officers about shooting looters in the Algiers section of New Orleans.

"Did you have any problems with looters," [sic] asked an officer.

"Not anymore," said Gleason.

"Not anymore?"

"They're all dead," said Gleason.

The officer asked, "What happened?"

"We shot them," said Gleason.

"How many did you shoot?

"Thirty-eight."

"Thirty-eight people? What did you do with the bodies?"

"We gave them to the Coast Guard," said Gleason."

h.t to

Aftermath News